cs231n 강의 노트 2장 Linear classification Support Vector, Softmax 정리

2장 Linear classification Support Vector, Softmax 정리

Linear Classification

In the last section we introduced the problem of Image Classification, which is the task of assigning a single label to an image from a fixed set of categories.

Moreover, we described the k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN) classifier which labels images by comparing them to (annotated) images from the training set.

As we saw, kNN has a number of disadvantages:

- 이전 세션에서 설명했던 이미지 분류에 대한 문제는 고정된 범주 집합에서 이미지에 단일 레이블을 할당하는 작업입니다.

- 또한, 훈련 세트의이미지와 비교하여 이미지를 레이블링하는 kNN(k-Nearest Neighbor) 분류기에 대해 설명했습니다

-

KNN은 문제점을 가지고 있다.

- The classifier must remember all of the training data and store it for future comparisons with the test data. This is space inefficient because datasets may easily be gigabytes in size.

-

Classifying a test image is expensive since it requires a comparison to all training images.

- 모든 훈련데이터을 저장하고 모든 훈련데이터와 테스트 데이터를 비교한다. 비 효율적인 공간을 차지한다. 왜냐하면 datasets는 쉽게 기가바이트까지 사이즈가 늘어날 수 있다.

- 테스트 이미지를 분류하려면 모든 훈련 이미지와 비교해야 하므로 비용이 많이 듭니다.

Overview. We are now going to develop a more powerful approach to image classification that we will eventually naturally extend to entire Neural Networks and Convolutional Neural Networks.

The approach will have two major components: a score function that maps the raw data to class scores, and a loss function that quantifies the agreement between the predicted scores and the ground truth labels.

We will then cast this as an optimization problem in which we will minimize the loss function with respect to the parameters of the score function.

- 궁극적으로 자연 스럽게 확정해 Neural Net, Conv Net 활용해 강력한 적근 방식으로 이미지 분류를 개발 해야한다.

- 중요한 접근 방식 2가지 중 하나는 행에 클래스 scores score function, 예측 점수와 실제 점수를 레이블간에 값을 정량화 한 값을 loss function 이라고 한다.

Parameterized mapping from images to label scores

The first component of this approach is to define the score function that maps the pixel values of an image to confidence scores for each class.

We will develop the approach with a concrete example. As before, let’s assume a training dataset of images \( x_i \in R^D \), each associated with a label \( y_i \).

Here \( i = 1 \dots N \) and \( y_i \in { 1 \dots K } \). That is, we have N examples (each with a dimensionality D) and K distinct categories.

For example, in CIFAR-10 we have a training set of N = 50,000 images, each with D = 32 x 32 x 3 = 3072 pixels, and K = 10, since there are 10 distinct classes (dog, cat, car, etc).

We will now define the score function \(f: R^D \mapsto R^K\) that maps the raw image pixels to class scores.

- 네트워크에 대한 첫번째 접근은 이미지를 결정하는 점수에 대한 특징의 픽셀 값을 맵핑 하는 score function 정의하는 것이다.

- 구체적인 방식으로 개발해야한다. 예를 들어 train dataset \( x_i \in R^D \) 쉽게 말해 이미 특징은 X_i 저장되고, \(yi\) 연관이 있다.

- \( i = 1 \dots N \) and \( y_i \in { 1 \dots K } \) 설명은 i는 1부터 N 개의 이미지가 존재하고, Y는 k개의 이미지 카테고리가 존재한다.

- 예를 들어 CIFAR-10 이미지에는 train set의 50,000 이미지가 N 개이다, 그리고 각각의 필셀은 32 x 32 x 3 = 3072 존재하고, K 이미지 분류는 10개의 카테고리가 있다.

- \(f: R^D \mapsto R^K\) 이미지의 특징들을 찾아 이미지 카테고리로 변경해야한다.

Linear classifier. In this module we will start out with arguably the simplest possible function, a linear mapping:

- 가장 간단한 선형 맵칭부터 시작한다.

In the above equation, we are assuming that the image \(x_i\) has all of its pixels flattened out to a single column vector of shape [D x 1].

The matrix W (of size [K x D]), and the vector b (of size [K x 1]) are the parameters of the function.

In CIFAR-10, \(x_i\) contains all pixels in the i-th image flattened into a single [3072 x 1] column, W is [10 x 3072] and b is [10 x 1], so 3072 numbers come into the function (the raw pixel values) and 10 numbers come out (the class scores).

The parameters in W are often called the weights, and b is called the bias vector because it influences the output scores, but without interacting with the actual data \(x_i\).

However, you will often hear people use the terms weights and parameters interchangeably.

There are a few things to note:

- 우리는 image 모든 픽셀을 펼치고 [D x 1] 단일 벡터로 표기하여 \(x_i\) 가지고 있다.

- W (of size [K x D]), b (of size [K x 1]) 값은 함수의 파라미터 값이다.

- \(x_i\) 값은 모든 특징을 펼친 값으로 단일 값이기에 [3072 x 1] 모양을 가지고, W is [10 x 3072], b is [10 x 1] 가진다. 3072는 raw 픽셀의 값들을 의미하고, 10 number class scores 값을 가진다.

- W는 weights 불리고, b bias vector 불러진다. 왜냐하면 output scores 두개는 영향을 주게된다. 그리고 \(x_i\) 상호작용하지 않는다.

- 사람들은 weights, parameters 두 개를 혼동해서 부른다.

First, note that the single matrix multiplication \(W x_i\) is effectively evaluating 10 separate classifiers in parallel (one for each class), where each classifier is a row of W.

Notice also that we think of the input data \( (x_i, y_i) \) as given and fixed, but we have control over the setting of the parameters W,b. Our goal will be to set these in such way that the computed scores match the ground truth labels across the whole training set. We will go into much more detail about how this is done, but intuitively we wish that the correct class has a score that is higher than the scores of incorrect classes.

An advantage of this approach is that the training data is used to learn the parameters W,b, but once the learning is complete we can discard the entire training set and only keep the learned parameters. That is because a new test image can be simply forwarded through the function and classified based on the computed scores.

Lastly, note that classifying the test image involves a single matrix multiplication and addition, which is significantly faster than comparing a test image to all training images.

- \(W x_i\) 행렬 곱을 하게 되면 10개의 각각의 score 점수를 계산하게 되고 W 모양중 앞에 있는 숫자가 분류에 대한 갯수이다. 우리의 목표는 계산된 점수가 전체 훈련 세트의 실제 레이블과 일치하도록 이를 설정하는 것입니다. 이것이 어떻게 수행되는지에 대해 더 자세히 설명하겠지만 직관적으로 우리는 올바른 클래스가 잘못된 클래스의 점수보다 높은 점수를 갖기를 바랍니다.

- input data \( (x_i, y_i) \) 고정인 값, 우리가 컨트롤해야 하는 값은 W,b.

- 이 접근 방식의 장점은 훈련 데이터가 W,b 매개변수를 학습하는 데 사용된다는 것입니다. 그러나 학습이 완료되면 전체 훈련 세트를 버리고 학습된 매개변수만 유지할 수 있습니다. 새로운 테스트 이미지가 함수를 통해 간단하게 전달되고 계산된 점수에 따라 분류될 수 있기 때문입니다.

- 마지막으로, 테스트 이미지 분류에는 단일 행렬 곱셈과 덧셈이 포함되는데, 이는 테스트 이미지를 모든 훈련 이미지와 비교하는 것보다 훨씬 빠릅니다.

Foreshadowing: Convolutional Neural Networks will map image pixels to scores exactly as shown above, but the mapping ( f ) will be more complex and will contain more parameters.

Interpreting a linear classifier

Notice that a linear classifier computes the score of a class as a weighted sum of all of its pixel values across all 3 of its color channels.

Depending on precisely what values we set for these weights, the function has the capacity to like or dislike (depending on the sign of each weight) certain colors at certain positions in the image.

For instance, you can imagine that the “ship” class might be more likely if there is a lot of blue on the sides of an image (which could likely correspond to water).

You might expect that the “ship” classifier would then have a lot of positive weights across its blue channel weights (presence of blue increases score of ship), and negative weights in the red/green channels (presence of red/green decreases the score of ship).

- 선형 분류기는 3개의 모든 색상 채널에 걸쳐 모든 픽셀 값의 가중치 합으로 클래스의 점수를 계산합니다.

- 이러한 가중치에 대해 설정한 값이 정확히 무엇인지에 따라 함수는 이미지의 특정 위치에서 특정 색상을 좋아하거나 싫어하거나(각 가중치의 부호에 따라) 수행할 수 있습니다.

- 예를 들어, 이미지의 측면에 파란색이 많이 있는 경우(물에 해당할 수 있음) “선박” 클래스의 가능성이 더 높을 수 있다고 상상할 수 있습니다.

- 그러면 “선박” 분류기가 파란색 채널 가중치(선박의 파란색 증가 점수의 존재)에 걸쳐 많은 양의 가중치를 가지고, 빨간색/녹색 채널의 음의 가중치(빨간색/녹색의 존재는 선박의 점수를 감소)를 가질 것으로 예상할 수 있습니다.

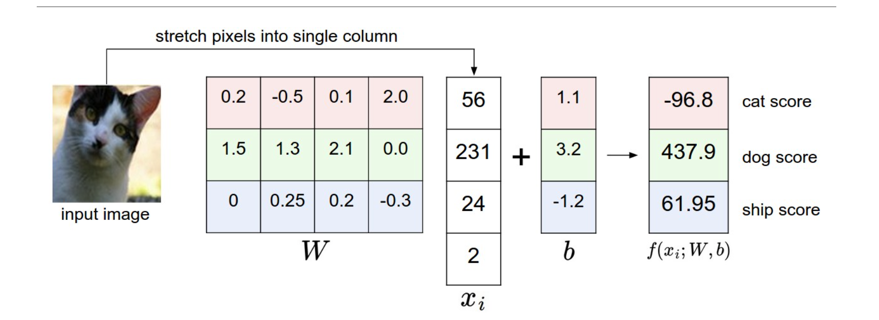

An example of mapping an image to class scores.

For the sake of visualization, we assume the image only has 4 pixels (4 monochrome pixels, we are not considering color channels in this example for brevity), and that we have 3 classes (red (cat), green (dog), blue (ship) class).

(Clarification: in particular, the colors here simply indicate 3 classes and are not related to the RGB channels.)

We stretch the image pixels into a column and perform matrix multiplication to get the scores for each class.

Note that this particular set of weights W is not good at all: the weights assign our cat image a very low cat score.

In particular, this set of weights seems convinced that it’s looking at a dog.

- 이미지를 클래스 점수에 매핑하는 예입니다. 시각화를 위해 이미지가 4개의 픽셀만 가지고 있다고 가정합니다(단색 픽셀 4개, 간결성을 위해 이 예에서는 컬러 채널을 고려하지 않음). 그리고 3개의 클래스(빨간색(고양이), 녹색(개), 파란색(배)가 있다고 가정합니다.)

- (명확화: 특히 여기서 색상은 단순히 3개의 클래스를 나타내며 RGB 채널과 관련이 없습니다.)

- 이미지 픽셀을 열로 늘리고 행렬 곱셈을 수행하여 각 클래스의 점수를 얻습니다. 이 특정한 가중치 집합 W는 전혀 좋지 않습니다.

- 가중치 집합은 고양이 이미지에 매우 낮은 고양이 점수를 부여합니다. 특히 이 가중치 집합은 개를 보고 있다는 것을 확신하는 것 같습니다.

Analogy of images as high-dimensional points.

Since the images are stretched into high-dimensional column vectors, we can interpret each image as a single point in this space (e.g. each image in CIFAR-10 is a point in 3072-dimensional space of 32x32x3 pixels).

Analogously, the entire dataset is a (labeled) set of points.

- 고차원 점으로 이미지를 유추합니다.

- 이미지를 고차원 열 벡터로 확장하기 때문에 각 이미지를 이 공간에서 단일 점으로 해석할 수 있습니다(예: CIFAR-10의 각 이미지는 32x32x3 픽셀의 3072차원 공간에 있는 점입니다).

- 마찬가지로 전체 데이터 집합은 (라벨로 표시된) 점 집합입니다.

Since we defined the score of each class as a weighted sum of all image pixels, each class score is a linear function over this space.

We cannot visualize 3072-dimensional spaces, but if we imagine squashing all those dimensions into only two dimensions, then we can try to visualize what the classifier might be doing:

- 각 클래스의 점수를 모든 이미지 픽셀의 가중 합으로 정의했기 때문에 각 클래스 점수는 이 공간에 대한 선형 함수입니다.

- 3072차원 공간을 시각화할 수는 없지만 이 모든 차원을 2차원으로만 압축하는 것을 상상하면 분류기가 무엇을 하는지 시각화할 수 있습니다:

As we saw above, every row of \(W\) is a classifier for one of the classes.

The geometric interpretation of these numbers is that as we change one of the rows of \(W\), the corresponding line in the pixel space will rotate in different directions.

The biases \(b\), on the other hand, allow our classifiers to translate the lines.

In particular, note that without the bias terms, plugging in \( x_i = 0 \) would always give score of zero regardless of the weights, so all lines would be forced to cross the origin.

- 위에서 본 것처럼, \(W\)의 모든 행은 클래스 중 하나의 클래스에 대한 분류기입니다.

- 이 숫자들의 기하학적 해석은 \(W\)의 행 중 하나를 변경하면 픽셀 공간에서 해당하는 선이 다른 방향으로 회전한다는 것입니다.

- 반면, 편향 \(b\)은 분류기가 선을 번역할 수 있도록 해줍니다.

- 특히 편향 항이 없으면 \( x_i = 0 \)를 꽂으면 가중치에 관계없이 항상 0점이 되므로 모든 선이 원점을 가로지르도록 강제됩니다.

Interpretation of linear classifiers as template matching.

Another interpretation for the weights \(W\) is that each row of \(W\) corresponds to a template (or sometimes also called a prototype) for one of the classes.

The score of each class for an image is then obtained by comparing each template with the image using an inner product (or dot product) one by one to find the one that “fits” best.

With this terminology, the linear classifier is doing template matching, where the templates are learned. Another way to think of it is that we are still effectively doing Nearest Neighbor, but instead of having thousands of training images we are only using a single image per class (although we will learn it, and it does not necessarily have to be one of the images in the training set), and we use the (negative) inner product as the distance instead of the L1 or L2 distance.

- 선형 분류기를 템플릿 매칭으로 해석.

- 가중치 \(W\)에 대한 또 다른 해석은 \(W\)의 각 행이 클래스 중 하나에 대한 템플릿(또는 프로토타입이라고도 함)에 해당한다는 것입니다.

- 이미지에 대한 각 클래스의 점수는 내부 곱(또는 dotype)을 사용하여 각 템플릿을 이미지와 하나씩 비교하여 가장 “적합한” 템플릿을 찾습니다.

- 이 용어를 사용하여 선형 분류기는 템플릿을 학습하는 템플릿 매칭을 수행합니다. 이를 생각할 수 있는 또 다른 방법은 여전히 가장 가까운 이웃을 효과적으로 수행하고 있지만 수천 개의 훈련 이미지 대신 클래스당 단일 이미지만 사용하고 있다는 것입니다(학습하겠지만 반드시 훈련 집합의 이미지 중 하나일 필요는 없습니다). 그리고 L1 또는 L2 거리 대신 (음의) 내부 곱을 거리로 사용합니다.

Additionally, note that the horse template seems to contain a two-headed horse, which is due to both left and right facing horses in the dataset.

The linear classifier merges these two modes of horses in the data into a single template.

Similarly, the car classifier seems to have merged several modes into a single template which has to identify cars from all sides, and of all colors.

In particular, this template ended up being red, which hints that there are more red cars in the CIFAR-10 dataset than of any other color.

The linear classifier is too weak to properly account for different-colored cars, but as we will see later neural networks will allow us to perform this task.

Looking ahead a bit, a neural network will be able to develop intermediate neurons in its hidden layers that could detect specific car types (e.g. green car facing left, blue car facing front, etc.), and neurons on the next layer could combine these into a more accurate car score through a weighted sum of the individual car detectors.

- 또한 말 템플릿에는 두 개의 머리를 가진 말이 포함되어 있는 것으로 보이는데, 이는 데이터 세트에서 왼쪽과 오른쪽 모두 말을 마주보고 있기 때문입니다.

- 선형 분류기는 데이터의 이 두 모드의 말을 단일 템플릿으로 통합합니다.

- 마찬가지로, 차량 분류기는 여러 모드를 모든 색상의 차량을 식별해야 하는 단일 템플릿으로 통합한 것으로 보입니다.

- 특히 이 템플릿은 빨간색으로 끝나게 되었는데, 이는 CIFAR-10 데이터 세트에 다른 어떤 색상의 차량보다 더 많은 빨간색 차량이 있다는 것을 암시합니다.

- 선형 분류기는 너무 약해서 다른 색상의 차량을 제대로 설명할 수 없지만, 나중에 알게 되겠지만 신경망을 통해 이 작업을 수행할 수 있습니다.

- 조금 앞을 내다보면, 신경망은 특정 차종(예: 녹색 차량 왼쪽, 파란색 차량 전방 등)을 감지할 수 있는 숨겨진 레이어에서 중간 뉴런을 개발할 수 있으며, 다음 레이어의 뉴런은 개별 차량 감지기의 가중 합계를 통해 이를 더 정확한 차량 점수로 결합할 수 있습니다.

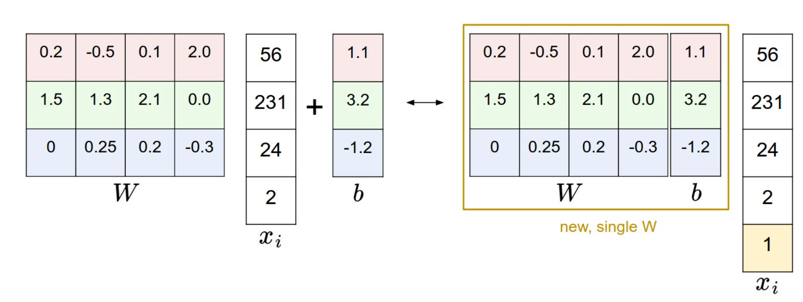

Bias trick. Before moving on we want to mention a common simplifying trick to representing the two parameters \(W,b\) as one. Recall that we defined the score function as:

- Bias trick. 계속 진행하기 전에 두 매개변수 \(W,b\)를 하나로 표현하는 일반적인 단순화 트릭을 언급하고 싶습니다. 점수 함수를 다음과 같이 정의했음을 기억하세요. \(f(x_i, W, b) = W x_i + b\)

As we proceed through the material it is a little cumbersome to keep track of two sets of parameters (the biases \(b\) and weights \(W\)) separately. A commonly used trick is to combine the two sets of parameters into a single matrix that holds both of them by extending the vector \(x_i\) with one additional dimension that always holds the constant \(1\) - a default bias dimension. With the extra dimension, the new score function will simplify to a single matrix multiply:

- 자료를 진행하면서 두 개의 매개변수 세트(바이어스 \(b\) 및 가중치 \(W\))를 개별적으로 추적하는 것은 약간 번거롭습니다. 일반적으로 사용되는 트릭은 벡터 \(x_i\)를 항상 상수 \(1\)을 유지하는 하나의 추가 차원으로 확장하여 두 매개변수 세트를 두 매개변수 세트를 모두 보유하는 단일 행렬로 결합하는 것입니다. 기본 편향 차원. 추가 차원을 사용하면 새로운 점수 함수가 단일 행렬 곱셈으로 단순화됩니다. \(f(x_i, W) = W x_i\)

With our CIFAR-10 example, \(x_i\) is now [3073 x 1] instead of [3072 x 1] - (with the extra dimension holding the constant 1), and \(W\) is now [10 x 3073] instead of [10 x 3072]. The extra column that \(W\) now corresponds to the bias \(b\). An illustration might help clarify:

- CIFAR-10 예에서 \(x_i\)는 이제 [3072 x 1] 대신 [3073 x 1]입니다(추가 차원은 상수 1을 유지함). 그리고 \(W\)는 이제 [10 x 3072] 대신 [10 x 3073]. 이제 \(W\)가 편향 \(b\)에 해당하는 추가 열입니다. 그림을 보면 다음 사항을 명확히 하는 데 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Image data preprocessing. As a quick note, in the examples above we used the raw pixel values (which range from [0…255]). In Machine Learning, it is a very common practice to always perform normalization of your input features (in the case of images, every pixel is thought of as a feature). In particular, it is important to center your data by subtracting the mean from every feature. In the case of images, this corresponds to computing a mean image across the training images and subtracting it from every image to get images where the pixels range from approximately [-127 … 127]. Further common preprocessing is to scale each input feature so that its values range from [-1, 1]. Of these, zero mean centering is arguably more important but we will have to wait for its justification until we understand the dynamics of gradient descent.

- 이미지 데이터 전처리.

- 참고로 위의 예에서는 원시 픽셀 값(범위: [0…255])을 사용했습니다. 머신러닝에서는 항상 입력 특징의 정규화를 수행하는 것이 매우 일반적인 관행입니다(이미지의 경우 모든 픽셀이 특징으로 간주됩니다).

- 특히 모든 특성에서 평균을 빼서 데이터를 중앙에 배치하는 것이 중요합니다. 이미지의 경우 이는 훈련 이미지 전체에 걸쳐 평균 이미지를 계산하고 모든 이미지에서 이를 빼서 픽셀 범위가 대략 [-127 … 127]인 이미지를 얻는 것에 해당합니다.

- 더욱 일반적인 전처리는 값이 [-1, 1] 범위가 되도록 각 입력 기능의 크기를 조정하는 것입니다. 이 중에서 제로 평균 센터링이 더 중요할 수는 있지만 경사하강법의 역학을 이해할 때까지 그 타당성을 기다려야 합니다.

Loss function

In the previous section we defined a function from the pixel values to class scores, which was parameterized by a set of weights \(W\).

Moreover, we saw that we don’t have control over the data \( (x_i,y_i) \) (it is fixed and given), but we do have control over these weights and we want to set them so that the predicted class scores are consistent with the ground truth labels in the training data.

- 이전 섹션에서 우리는 픽셀 값에서 클래스 점수까지의 함수를 정의했는데, 이는 가중치 세트 \(W\)로 매개변수화되었습니다.

- 게다가 우리는 데이터 \( (x_i,y_i) \)(고정되어 있고 제공됨)를 제어할 수 없다는 것을 알았지만 이러한 가중치를 제어할 수 있으며 다음과 같이 설정하려고 합니다. 예측된 클래스 점수는 훈련 데이터의 정답 레이블과 일치합니다.

For example, going back to the example image of a cat and its scores for the classes “cat”, “dog” and “ship”, we saw that the particular set of weights in that example was not very good at all:

We fed in the pixels that depict a cat but the cat score came out very low (-96.8) compared to the other classes (dog score 437.9 and ship score 61.95).

We are going to measure our unhappiness with outcomes such as this one with a loss function (or sometimes also referred to as the cost function or the objective).

Intuitively, the loss will be high if we’re doing a poor job of classifying the training data, and it will be low if we’re doing well.

- 예를 들어, 고양이의 예제 이미지와 “cat”, “dog” 및 “ship” 클래스에 대한 점수로 돌아가면 해당 예제의 특정 가중치 집합이 전혀 좋지 않다는 것을 알 수 있습니다.

- 고양이를 묘사한 픽셀에서는 고양이 점수가 다른 클래스(개 점수 437.9, 배 점수 61.95)에 비해 매우 낮은 점수(-96.8)로 나타났습니다.

- 우리는 손실 함수(또는 비용 함수 또는 목표라고도 함)를 사용하여 이와 같은 결과에 대한 불행을 측정할 것입니다.

- 직관적으로 훈련 데이터를 제대로 분류하지 못하면 손실이 높을 것이고, 잘 분류하면 손실이 낮을 것입니다.

Multiclass Support Vector Machine loss

There are several ways to define the details of the loss function.

As a first example we will first develop a commonly used loss called the Multiclass Support Vector Machine (SVM) loss.

The SVM loss is set up so that the SVM “wants” the correct class for each image to a have a score higher than the incorrect classes by some fixed margin \(\Delta\).

Notice that it’s sometimes helpful to anthropomorphise the loss functions as we did above: The SVM “wants” a certain outcome in the sense that the outcome would yield a lower loss (which is good).

- 손실 함수의 세부 사항을 정의하는 방법에는 여러 가지가 있습니다.

- 첫 번째 예로 Multiclass Support Vector Machine (SVM) 손실이라는 일반적으로 사용되는 손실을 먼저 개발하겠습니다.

- SVM 손실은 SVM이 각 이미지에 대한 올바른 클래스가 고정된 마진 \(\Delta\)만큼 잘못된 클래스보다 높은 점수를 갖도록 “원”하도록 설정됩니다.

- 위에서 했던 것처럼 손실 함수를 의인화하는 것이 때로는 도움이 된다는 점에 유의하세요. SVM은 결과가 더 낮은 손실을 낳는다는 의미에서 특정 결과를 “원합니다”(좋은 결과입니다).

Let’s now get more precise.

Recall that for the i-th example we are given the pixels of image \( x_i \) and the label \( y_i \) that specifies the index of the correct class.

The score function takes the pixels and computes the vector \( f(x_i, W) \) of class scores,

which we will abbreviate to \(s\) (short for scores). For example, the score for the j-th class is the j-th element: \( s_j = f(x_i, W)_j \). The Multiclass SVM loss for the i-th example is then formalized as follows:

- 이제 좀 더 정확하게 알아보겠습니다.

- i번째 예에서는 이미지 픽셀 \( x_i \)과 올바른 클래스의 인덱스를 지정하는 레이블 \( y_i \)가 제공된다는 점을 기억하세요.

- 점수 함수는 픽셀을 가져와 클래스 점수의 벡터 \( f(x_i, W) \)를 계산합니다.

- 이를 \(s\)(점수의 약어)로 축약합니다. 예를 들어, j번째 클래스의 점수는 j번째 요소입니다: \( s_j = f(x_i, W)_j \). i번째 예에 대한 다중클래스 SVM 손실은 다음과 같이 공식화됩니다.

Example. Lets unpack this with an example to see how it works.

Suppose that we have three classes that receive the scores \( s = [13, -7, 11]\), and that the first class is the true class (i.e. \(y_i = 0\)).

Also assume that \(\Delta\) (a hyperparameter we will go into more detail about soon) is 10. The expression above sums over all incorrect classes (\(j \neq y_i\)), so we get two terms:

- 예시.

- 예제를 통해 이것이 어떻게 작동하는지 살펴보겠습니다.

- \( s = [13, -7, 11]\) 점수를 받는 세 개의 클래스가 있고 첫 번째 클래스가 실제 클래스(예: \(y_i = 0\))라고 가정합니다.

- 또한 \(\Delta\)(곧 자세히 설명할 하이퍼파라미터)가 10이라고 가정합니다. 위의 표현식은 모든 잘못된 클래스(\(j \neq y_i\))의 합을 계산하므로 다음을 얻습니다. 두 가지 용어:

You can see that the first term gives zero since [-7 - 13 + 10] gives a negative number, which is then thresholded to zero with the \(max(0,-)\) function.

We get zero loss for this pair because the correct class score (13) was greater than the incorrect class score (-7) by at least the margin 10. In fact the difference was 20, which is much greater than 10 but the SVM only cares that the difference is at least 10; Any additional difference above the margin is clamped at zero with the max operation.

The second term computes [11 - 13 + 10] which gives 8.

That is, even though the correct class had a higher score than the incorrect class (13 > 11), it was not greater by the desired margin of 10.

The difference was only 2, which is why the loss comes out to 8 (i.e. how much higher the difference would have to be to meet the margin).

In summary, the SVM loss function wants the score of the correct class \(y_i\) to be larger than the incorrect class scores by at least by \(\Delta\) (delta). If this is not the case, we will accumulate loss.

- [-7 - 13 + 10]이 음수를 제공하므로 첫 번째 항이 0을 제공하고 \(max(0,-)\) 함수를 사용하여 0으로 임계값이 지정되는 것을 볼 수 있습니다.

- 올바른 클래스 점수(13)가 잘못된 클래스 점수(-7)보다 최소한 마진 10만큼 더 크기 때문에 이 쌍에 대한 손실은 0입니다. 실제로 차이는 20이었고 이는 10보다 훨씬 컸지만 SVM만 해당됩니다.

- 차이가 10 이상인지 확인합니다. 마진을 초과하는 추가 차이는 max 작업을 통해 0으로 고정됩니다.

- 두 번째 항은 [11 - 13 + 10]을 계산하여 8을 제공합니다. 즉, 올바른 클래스가 잘못된 클래스보다 높은 점수를 가지더라도(13 > 11) 원하는 마진인 10만큼 크지 않습니다.

- 차이 2에 불과하므로 손실이 8이 됩니다(즉, 마진을 충족하려면 차이가 얼마나 커야 하는지).

- 요약하면, SVM 손실 함수는 올바른 클래스 \(y_i\)의 점수가 잘못된 클래스 점수보다 최소한 \(\Delta\)(델타)만큼 커지기를 원합니다. 그렇지 않으면 손실이 누적될 것입니다.

Note that in this particular module we are working with linear score functions ( \( f(x_i; W) = W x_i \) ), so we can also rewrite the loss function in this equivalent form:

- 이 특정 모듈에서는 선형 점수 함수( \( f(x_i; W) = W x_i \) )로 작업하므로 손실 함수를 다음과 같은 형식으로 다시 작성할 수도 있습니다.

where \(w_j\) is the j-th row of \(W\) reshaped as a column. However, this will not necessarily be the case once we start to consider more complex forms of the score function \(f\).

- 여기서 \(w_j\)는 열로 모양이 변경된 \(W\)의 j번째 행입니다.

- 그러나 점수 함수 \(f\)의 더 복잡한 형태를 고려하기 시작하면 반드시 그런 것은 아닙니다.

A last piece of terminology we’ll mention before we finish with this section is that the threshold at zero \(max(0,-)\) function is often called the hinge loss.

You’ll sometimes hear about people instead using the squared hinge loss SVM (or L2-SVM), which uses the form \(max(0,-)^2\) that penalizes violated margins more strongly (quadratically instead of linearly). The unsquared version is more standard, but in some datasets the squared hinge loss can work better.

This can be determined during cross-validation.

- 이 섹션을 마치기 전에 언급할 마지막 용어는 0 \(max(0,-)\) 함수의 임계값을 힌지 손실이라고 부르는 경우가 많다는 것입니다.

- 위반된 마진에 더 강력한 페널티를 적용하는 \(max(0,-)^2\) 형식을 사용하는 제곱 경첩 손실 SVM(또는 L2-SVM)을 대신 사용하는 사람들에 대해 듣게 될 것입니다(선형이 아닌 2차적으로). ). 제곱되지 않은 버전이 더 표준적이지만 일부 데이터세트에서는 제곱된 힌지 손실이 더 잘 작동할 수 있습니다.

- 이는 교차 검증 중에 결정될 수 있습니다.

Regularization. There is one bug with the loss function we presented above.

Suppose that we have a dataset and a set of parameters W that correctly classify every example (i.e. all scores are so that all the margins are met, and \(L_i = 0\) for all i).

The issue is that this set of W is not necessarily unique: there might be many similar W that correctly classify the examples.

One easy way to see this is that if some parameters W correctly classify all examples (so loss is zero for each example), then any multiple of these parameters \( \lambda W \) where \( \lambda > 1 \) will also give zero loss because this transformation uniformly stretches all score magnitudes and hence also their absolute differences.

For example, if the difference in scores between a correct class and a nearest incorrect class was 15, then multiplying all elements of W by 2 would make the new difference 30.

- 정규화. 위에서 제시한 손실 함수에는 버그가 하나 있습니다.

- 모든 예를 정확하게 분류하는 데이터 세트와 매개변수 W 세트가 있다고 가정합니다(즉, 모든 점수는 모든 마진이 충족되도록 하고 모든 i에 대해 \(L_i = 0\)입니다).

- 문제는 이 W 세트가 반드시 고유하지는 않다는 것입니다. 예를 올바르게 분류하는 유사한 W가 많이 있을 수 있습니다.

- 이를 쉽게 확인할 수 있는 한 가지 방법은 일부 매개변수 W가 모든 예를 올바르게 분류하는 경우(따라서 각 예의 손실은 0임) 이러한 매개변수 중 임의의 배수가 \( \lambda W \)인 경우 \( \ lambda > 1 \) 또한 이 변환은 모든 점수 크기와 절대 차이를 균일하게 확장하므로 손실이 0이 됩니다.

- 예를 들어, 올바른 클래스와 가장 가까운 잘못된 클래스 간의 점수 차이가 15인 경우 W의 모든 요소에 2를 곱하면 새로운 차이가 30이 됩니다.

In other words, we wish to encode some preference for a certain set of weights W over others to remove this ambiguity. We can do so by extending the loss function with a regularization penalty \(R(W)\). The most common regularization penalty is the squared L2 norm that discourages large weights through an elementwise quadratic penalty over all parameters:

- 즉, 우리는 이러한 모호성을 제거하기 위해 다른 가중치보다 W 특정 가중치 집합에 대한 선호도를 인코딩하려고 합니다.

- 정규화 페널티 \(R(W)\)를 사용하여 손실 함수를 확장하면 그렇게 할 수 있습니다.

- 가장 일반적인 정규화 페널티는 모든 매개변수에 대한 요소별 2차 페널티를 통해 큰 가중치를 방지하는 제곱 L2 표준입니다.

In the expression above, we are summing up all the squared elements of \(W\). Notice that the regularization function is not a function of the data, it is only based on the weights. Including the regularization penalty completes the full Multiclass Support Vector Machine loss, which is made up of two components: the data loss (which is the average loss \(L_i\) over all examples) and the regularization loss. That is, the full Multiclass SVM loss becomes:

- 위의 표현에서는 \(W\)의 모든 제곱 요소를 합산합니다.

- 정규화 함수는 데이터의 함수가 아니라 가중치만을 기반으로 한다는 점에 유의하세요.

- 정규화 페널티를 포함하면 데이터 손실(모든 예에 대한 평균 손실\(L_i\))과 정규화의 두 가지 구성 요소로 구성된 전체 멀티클래스 지원 벡터 머신 손실이 완료됩니다. 손실.

- 즉, 전체 멀티클래스 SVM 손실은 다음과 같습니다.

Or expanding this out in its full form:

\[L = \frac{1}{N} \sum_i \sum_{j\neq y_i} \left[ \max(0, f(x_i; W)_j - f(x_i; W)_{y_i} + \Delta) \right] + \lambda \sum_k\sum_l W_{k,l}^2\]Where \(N\) is the number of training examples. As you can see, we append the regularization penalty to the loss objective, weighted by a hyperparameter \(\lambda\). There is no simple way of setting this hyperparameter and it is usually determined by cross-validation.

- 여기서 \(N\)은 학습 예제의 수입니다.

- 보시다시피, 우리는 하이퍼파라미터 \(\lambda\)에 의해 가중치가 부여된 손실 목표에 정규화 페널티를 추가합니다.

- 이 하이퍼파라미터를 설정하는 간단한 방법은 없으며 일반적으로 교차 검증을 통해 결정됩니다.

In addition to the motivation we provided above there are many desirable properties to include the regularization penalty, many of which we will come back to in later sections. For example, it turns out that including the L2 penalty leads to the appealing max margin property in SVMs (See CS229 lecture notes for full details if you are interested).

- 위에서 제공한 동기 외에도 정규화 페널티를 포함하는 바람직한 속성이 많이 있으며, 그 중 많은 부분은 이후 섹션에서 다시 설명하겠습니다.

- 예를 들어, L2 페널티를 포함하면 SVM의 매력적인 최대 마진 속성으로 이어지는 것으로 나타났습니다(CS229 강의 노트 참조 관심이 있으시면 자세한 내용을 확인하세요).

The most appealing property is that penalizing large weights tends to improve generalization, because it means that no input dimension can have a very large influence on the scores all by itself. For example, suppose that we have some input vector \(x = [1,1,1,1] \) and two weight vectors \(w_1 = [1,0,0,0]\), \(w_2 = [0.25,0.25,0.25,0.25] \). Then \(w_1^Tx = w_2^Tx = 1\) so both weight vectors lead to the same dot product, but the L2 penalty of \(w_1\) is 1.0 while the L2 penalty of \(w_2\) is only 0.5. Therefore, according to the L2 penalty the weight vector \(w_2\) would be preferred since it achieves a lower regularization loss. Intuitively, this is because the weights in \(w_2\) are smaller and more diffuse. Since the L2 penalty prefers smaller and more diffuse weight vectors, the final classifier is encouraged to take into account all input dimensions to small amounts rather than a few input dimensions and very strongly. As we will see later in the class, this effect can improve the generalization performance of the classifiers on test images and lead to less overfitting.

가장 매력적인 속성은 큰 가중치에 페널티를 적용하면 일반화가 향상되는 경향이 있다는 것입니다. 이는 입력 차원 자체가 점수에 매우 큰 영향을 미칠 수 없음을 의미하기 때문입니다. 예를 들어 입력 벡터 \(x = [1,1,1,1] \)와 두 개의 가중치 벡터 \(w_1 = [1,0,0,0]\), \가 있다고 가정합니다. (w_2 = [0.25,0.25,0.25,0.25] \). 그런 다음 \(w_1^Tx = w_2^Tx = 1\)이므로 두 가중치 벡터는 모두 동일한 내적으로 이어지지만 L2 페널티는 \(w_1\)이고 L2 페널티는 \(w_2 \)은 0.5에 불과합니다. 따라서 L2 페널티에 따르면 가중치 벡터 \(w_2\)가 더 낮은 정규화 손실을 달성하므로 선호됩니다. 직관적으로 이는 \(w_2\)의 가중치가 더 작고 더 분산되어 있기 때문입니다. L2 페널티는 더 작고 분산된 가중치 벡터를 선호하므로 최종 분류자는 몇 가지 입력 차원을 매우 강력하게 고려하는 대신 모든 입력 차원을 소량으로 고려하는 것이 좋습니다. 나중에 수업에서 살펴보겠지만, 이 효과는 테스트 이미지에 대한 분류기의 일반화 성능을 향상시키고 과적합을 줄일 수 있습니다.

Note that biases do not have the same effect since, unlike the weights, they do not control the strength of influence of an input dimension. Therefore, it is common to only regularize the weights \(W\) but not the biases \(b\). However, in practice this often turns out to have a negligible effect. Lastly, note that due to the regularization penalty we can never achieve loss of exactly 0.0 on all examples, because this would only be possible in the pathological setting of \(W = 0\).

- 편향은 가중치와 달리 입력 차원의 영향 강도를 제어하지 않기 때문에 동일한 효과를 갖지 않습니다.

- 따라서 가중치 \(W\)만 정규화하고 편향 \(b\)는 정규화하지 않는 것이 일반적입니다. 그러나 실제로는 이는 무시할만한 효과를 갖는 것으로 판명됩니다.

- 마지막으로 정규화 페널티로 인해 모든 예에서 정확히 0.0의 손실을 달성할 수 없습니다. 이는 \(W = 0\)의 병리학적 설정에서만 가능하기 때문입니다.

def L_i(x, y, W):

"""

unvectorized version. Compute the multiclass svm loss for a single example (x,y)

- x is a column vector representing an image (e.g. 3073 x 1 in CIFAR-10)

with an appended bias dimension in the 3073-rd position (i.e. bias trick)

- y is an integer giving index of correct class (e.g. between 0 and 9 in CIFAR-10)

- W is the weight matrix (e.g. 10 x 3073 in CIFAR-10)

"""

delta = 1.0 # see notes about delta later in this section

scores = W.dot(x) # scores becomes of size 10 x 1, the scores for each class

correct_class_score = scores[y]

D = W.shape[0] # number of classes, e.g. 10

loss_i = 0.0

for j in range(D): # iterate over all wrong classes

if j == y:

# skip for the true class to only loop over incorrect classes

continue

# accumulate loss for the i-th example

loss_i += max(0, scores[j] - correct_class_score + delta)

return loss_i

def L_i_vectorized(x, y, W):

"""

A faster half-vectorized implementation. half-vectorized

refers to the fact that for a single example the implementation contains

no for loops, but there is still one loop over the examples (outside this function)

"""

delta = 1.0

scores = W.dot(x)

# compute the margins for all classes in one vector operation

margins = np.maximum(0, scores - scores[y] + delta)

# on y-th position scores[y] - scores[y] canceled and gave delta. We want

# to ignore the y-th position and only consider margin on max wrong class

margins[y] = 0

loss_i = np.sum(margins)

return loss_i

def L(X, y, W):

"""

fully-vectorized implementation :

- X holds all the training examples as columns (e.g. 3073 x 50,000 in CIFAR-10)

- y is array of integers specifying correct class (e.g. 50,000-D array)

- W are weights (e.g. 10 x 3073)

"""

# evaluate loss over all examples in X without using any for loops

# left as exercise to reader in the assignment

Practical Considerations

Setting Delta. Note that we brushed over the hyperparameter \(\Delta\) and its setting.

What value should it be set to, and do we have to cross-validate it?

It turns out that this hyperparameter can safely be set to \(\Delta = 1.0\) in all cases.

The hyperparameters \(\Delta\) and \(\lambda\) seem like two different hyperparameters, but in fact they both control the same tradeoff: The tradeoff between the data loss and the regularization loss in the objective.

The key to understanding this is that the magnitude of the weights \(W\) has direct effect on the scores (and hence also their differences): As we shrink all values inside \(W\) the score differences will become lower, and as we scale up the weights the score differences will all become higher.

Therefore, the exact value of the margin between the scores (e.g. \(\Delta = 1\), or \(\Delta = 100\)) is in some sense meaningless because the weights can shrink or stretch the differences arbitrarily. Hence, the only real tradeoff is how large we allow the weights to grow (through the regularization strength \(\lambda\)).

- 델타 설정. 초매개변수 \(\Delta\)와 해당 설정을 살펴보았습니다.

- 어떤 값으로 설정해야 하며, 교차 검증을 해야 합니까? 이 하이퍼파라미터는 모든 경우에 안전하게 \(\Delta = 1.0\)으로 설정될 수 있는 것으로 나타났습니다.

- 하이퍼파라미터 \(\Delta\) 및 \(\lambda\)는 서로 다른 두 하이퍼파라미터처럼 보이지만 사실 둘 다 동일한 트레이드오프, 즉 목표의 데이터 손실과 정규화 손실 간의 트레이드오프를 제어합니다.

- 이를 이해하는 열쇠는 가중치 \(W\)의 크기가 점수에 직접적인 영향을 미친다는 것입니다(따라서 그 차이도 마찬가지입니다). \(W\) 내부의 모든 값을 축소하면 점수 차이가 더 낮아지고 가중치를 높이면 점수 차이가 모두 더 높아질 것입니다.

- 따라서 점수 간 여백의 정확한 값(예: \(\Delta = 1\) 또는 \(\Delta = 100\))은 가중치가 차이를 줄이거나 늘릴 수 있으므로 어떤 의미에서는 의미가 없습니다. 임의로. ‘따라서 유일한 실제 절충안은 정규화 강도 \(\lambda\)를 통해 가중치를 얼마나 크게 늘릴 수 있는지입니다.

Relation to Binary Support Vector Machine. You may be coming to this class with previous experience with Binary Support Vector Machines, where the loss for the i-th example can be written as:

- 여러분은 이진 지원 벡터 머신에 대한 이전 경험을 가지고 이 수업을 듣게 될 것입니다. 여기서 i번째 예제의 손실은 다음과 같이 작성할 수 있습니다.

where \(C\) is a hyperparameter, and \(y_i \in \{ -1,1 \} \). You can convince yourself that the formulation we presented in this section contains the binary SVM as a special case when there are only two classes. That is, if we only had two classes then the loss reduces to the binary SVM shown above. Also, \(C\) in this formulation and \(\lambda\) in our formulation control the same tradeoff and are related through reciprocal relation \(C \propto \frac{1}{\lambda}\).

- 여기서 \(C\)는 하이퍼파라미터이고 \(y_i \in \{ -1,1 \} \)입니다. 이 섹션에서 제시한 공식에는 클래스가 두 개만 있는 경우의 특별한 경우로 이진 SVM이 포함되어 있음을 스스로 확신할 수 있습니다.

- 즉, 클래스가 두 개만 있는 경우 위에 표시된 이진 SVM으로 손실이 줄어듭니다. 또한 이 공식의 \(C\)와 우리 공식의 \(\lambda\)는 동일한 트레이드오프를 제어하며 상호 관계 \(C \propto \frac{1}{\lambda}\)를 통해 관련됩니다.

Aside: Optimization in primal.

If you’re coming to this class with previous knowledge of SVMs, you may have also heard of kernels, duals, the SMO algorithm, etc.

In this class (as is the case with Neural Networks in general) we will always work with the optimization objectives in their unconstrained primal form.

Many of these objectives are technically not differentiable (e.g. the max(x,y) function isn’t because it has a kink when x=y), but in practice this is not a problem and it is common to use a subgradient.

- Aside: Optimization in primal.

- SVM에 대한 사전 지식을 갖고 이 수업을 듣는다면 커널, 이중, SMO 알고리즘 등에 대해서도 들어봤을 것입니다.

- 이 수업에서는(일반적으로 신경망의 경우와 마찬가지로) 항상 제약이 없는 원시 형태의 최적화 목표.

- 이러한 목표 중 다수는 기술적으로 미분 불가능합니다(예: max(x,y) 함수는 x=y일 때 꼬임이 있기 때문에 미분 가능하지 않습니다). 그러나 실제로는 문제가 되지 않으며 하위 그라데이션을 사용하는 것이 일반적입니다. .

Softmax classifier

It turns out that the SVM is one of two commonly seen classifiers.

The other popular choice is the Softmax classifier, which has a different loss function.

If you’ve heard of the binary Logistic Regression classifier before, the Softmax classifier is its generalization to multiple classes.

Unlike the SVM which treats the outputs \(f(x_i,W)\) as (uncalibrated and possibly difficult to interpret) scores for each class, the Softmax classifier gives a slightly more intuitive output (normalized class probabilities) and also has a probabilistic interpretation that we will describe shortly.

In the Softmax classifier, the function mapping \(f(x_i; W) = W x_i\) stays unchanged, but we now interpret these scores as the unnormalized log probabilities for each class and replace the hinge loss with a cross-entropy loss that has the form:

- SVM은 흔히 볼 수 있는 두 가지 분류기 중 하나임이 밝혀졌습니다.

- 또 다른 인기 있는 선택은 다른 손실 함수를 갖는 Softmax 분류기입니다.

- 이전에 이진 로지스틱 회귀 분류기에 대해 들어본 적이 있다면 Softmax 분류기는 여러 클래스에 대한 일반화입니다.

- 출력 \(f(x_i,W)\)을 각 클래스에 대한 (보정되지 않고 해석하기 어려운) 점수로 처리하는 SVM과 달리 Softmax 분류기는 약간 더 직관적인 출력(정규화된 클래스 확률)을 제공하며 다음을 제공합니다.

- 곧 설명할 확률론적 해석입니다. Softmax 분류기에서 함수 매핑 \(f(x_i; W) = W x_i\)는 변경되지 않았지만 이제 이러한 점수를 각 클래스에 대한 정규화되지 않은 로그 확률로 해석하고 hinge loss로 대체합니다. cross-entropy loss 형식은 다음과 같습니다.

where we are using the notation \(f_j\) to mean the j-th element of the vector of class scores \(f\).

As before, the full loss for the dataset is the mean of \(L_i\) over all training examples together with a regularization term \(R(W)\).

The function \(f_j(z) = \frac{e^{z_j}}{\sum_k e^{z_k}} \) is called the softmax function: It takes a vector of arbitrary real-valued scores (in \(z\)) and squashes it to a vector of values between zero and one that sum to one.

The full cross-entropy loss that involves the softmax function might look scary if you’re seeing it for the first time but it is relatively easy to motivate.

- 여기서 우리는 클래스 점수 벡터 \(f\)의 j번째 요소를 의미하기 위해 \(f_j\) 표기법을 사용하고 있습니다.

- 이전과 마찬가지로 데이터 세트의 전체 손실은 정규화 용어 \(R(W)\)와 함께 모든 훈련 예제에 대한 평균 \(L_i\)입니다.

- \(f_j(z) = \frac{e^{z_j}}{\sum_k e^{z_k}} \) 함수는 softmax function라고 합니다.

- 이 함수는 임의의 실수 값의 벡터를 취합니다. (\(z\))에 점수를 매기고 합이 1이 되는 0과 1 사이의 값으로 구성된 벡터로 압축합니다.

- 소프트맥스 기능과 관련된 전체 교차 엔트로피 손실은 처음 보는 경우 무섭게 보일 수 있지만 동기를 부여하기는 상대적으로 쉽습니다.

Information theory view. The cross-entropy between a “true” distribution \(p\) and an estimated distribution \(q\) is defined as:

\[H(p,q) = - \sum_x p(x) \log q(x)\]The Softmax classifier is hence minimizing the cross-entropy between the estimated class probabilities ( \(q = e^{f_{y_i}} / \sum_j e^{f_j} \) as seen above) and the “true” distribution, which in this interpretation is the distribution where all probability mass is on the correct class (i.e. \(p = [0, \ldots 1, \ldots, 0]\) contains a single 1 at the \(y_i\) -th position.). Moreover, since the cross-entropy can be written in terms of entropy and the Kullback-Leibler divergence as \(H(p,q) = H(p) + D_{KL}(p||q)\), and the entropy of the delta function \(p\) is zero, this is also equivalent to minimizing the KL divergence between the two distributions (a measure of distance). In other words, the cross-entropy objective wants the predicted distribution to have all of its mass on the correct answer.

- 따라서 Softmax 분류기는 추정된 클래스 확률(위에서 볼 수 있듯이 \(q = e^{f_{y_i}} / \sum_j e^{f_j} \))과 “참” 분포 사이의 교차 엔트로피를 최소화합니다.

- 이 해석에서는 모든 확률 질량이 올바른 클래스에 있는 분포입니다(예: \(p = [0, \ldots 1, \ldots, 0]\)는 \(y_i\)에 단일 1을 포함합니다. j번째 위치.).

- 게다가 교차 엔트로피는 엔트로피와 Kullback-Leibler 발산의 관점에서 다음과 같이 쓸 수 있기 때문에 \(H(p,q) = H(p) + D_{KL}(p||q)\), 델타 함수 \(p\)의 엔트로피는 0입니다.

- 이는 두 분포(거리 측정) 간의 KL 발산을 최소화하는 것과도 동일합니다. 즉, 교차 엔트로피 목표는 예측 분포가 정답에 대한 모든 질량을 갖기를 원합니다.

Probabilistic interpretation. Looking at the expression, we see that

\[P(y_i \mid x_i; W) = \frac{e^{f_{y_i}}}{\sum_j e^{f_j} }\]can be interpreted as the (normalized) probability assigned to the correct label \(y_i\) given the image \(x_i\) and parameterized by \(W\). To see this, remember that the Softmax classifier interprets the scores inside the output vector \(f\) as the unnormalized log probabilities. Exponentiating these quantities therefore gives the (unnormalized) probabilities, and the division performs the normalization so that the probabilities sum to one. In the probabilistic interpretation, we are therefore minimizing the negative log likelihood of the correct class, which can be interpreted as performing Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). A nice feature of this view is that we can now also interpret the regularization term \(R(W)\) in the full loss function as coming from a Gaussian prior over the weight matrix \(W\), where instead of MLE we are performing the Maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimation. We mention these interpretations to help your intuitions, but the full details of this derivation are beyond the scope of this class.

Practical issues: Numeric stability. When you’re writing code for computing the Softmax function in practice, the intermediate terms \(e^{f_{y_i}}\) and \(\sum_j e^{f_j}\) may be very large due to the exponentials. Dividing large numbers can be numerically unstable, so it is important to use a normalization trick. Notice that if we multiply the top and bottom of the fraction by a constant \(C\) and push it into the sum, we get the following (mathematically equivalent) expression:

\[\frac{e^{f_{y_i}}}{\sum_j e^{f_j}} = \frac{Ce^{f_{y_i}}}{C\sum_j e^{f_j}} = \frac{e^{f_{y_i} + \log C}}{\sum_j e^{f_j + \log C}}\]We are free to choose the value of \(C\). This will not change any of the results, but we can use this value to improve the numerical stability of the computation. A common choice for \(C\) is to set \(\log C = -\max_j f_j \). This simply states that we should shift the values inside the vector \(f\) so that the highest value is zero. In code:

f = np.array([123, 456, 789]) # example with 3 classes and each having large scores

p = np.exp(f) / np.sum(np.exp(f)) # Bad: Numeric problem, potential blowup

# instead: first shift the values of f so that the highest number is 0:

f -= np.max(f) # f becomes [-666, -333, 0]

p = np.exp(f) / np.sum(np.exp(f)) # safe to do, gives the correct answer

Possibly confusing naming conventions. To be precise, the SVM classifier uses the hinge loss, or also sometimes called the max-margin loss. The Softmax classifier uses the cross-entropy loss. The Softmax classifier gets its name from the softmax function, which is used to squash the raw class scores into normalized positive values that sum to one, so that the cross-entropy loss can be applied. In particular, note that technically it doesn’t make sense to talk about the “softmax loss”, since softmax is just the squashing function, but it is a relatively commonly used shorthand.

SVM vs. Softmax

A picture might help clarify the distinction between the Softmax and SVM classifiers:

Softmax classifier provides “probabilities” for each class. Unlike the SVM which computes uncalibrated and not easy to interpret scores for all classes, the Softmax classifier allows us to compute “probabilities” for all labels. For example, given an image the SVM classifier might give you scores [12.5, 0.6, -23.0] for the classes “cat”, “dog” and “ship”. The softmax classifier can instead compute the probabilities of the three labels as [0.9, 0.09, 0.01], which allows you to interpret its confidence in each class. The reason we put the word “probabilities” in quotes, however, is that how peaky or diffuse these probabilities are depends directly on the regularization strength \(\lambda\) - which you are in charge of as input to the system. For example, suppose that the unnormalized log-probabilities for some three classes come out to be [1, -2, 0]. The softmax function would then compute:

\[[1, -2, 0] \rightarrow [e^1, e^{-2}, e^0] = [2.71, 0.14, 1] \rightarrow [0.7, 0.04, 0.26]\]Where the steps taken are to exponentiate and normalize to sum to one. Now, if the regularization strength \(\lambda\) was higher, the weights \(W\) would be penalized more and this would lead to smaller weights. For example, suppose that the weights became one half smaller ([0.5, -1, 0]). The softmax would now compute:

\[[0.5, -1, 0] \rightarrow [e^{0.5}, e^{-1}, e^0] = [1.65, 0.37, 1] \rightarrow [0.55, 0.12, 0.33]\]where the probabilites are now more diffuse. Moreover, in the limit where the weights go towards tiny numbers due to very strong regularization strength \(\lambda\), the output probabilities would be near uniform. Hence, the probabilities computed by the Softmax classifier are better thought of as confidences where, similar to the SVM, the ordering of the scores is interpretable, but the absolute numbers (or their differences) technically are not.

In practice, SVM and Softmax are usually comparable. The performance difference between the SVM and Softmax are usually very small, and different people will have different opinions on which classifier works better. Compared to the Softmax classifier, the SVM is a more local objective, which could be thought of either as a bug or a feature. Consider an example that achieves the scores [10, -2, 3] and where the first class is correct. An SVM (e.g. with desired margin of \(\Delta = 1\)) will see that the correct class already has a score higher than the margin compared to the other classes and it will compute loss of zero. The SVM does not care about the details of the individual scores: if they were instead [10, -100, -100] or [10, 9, 9] the SVM would be indifferent since the margin of 1 is satisfied and hence the loss is zero. However, these scenarios are not equivalent to a Softmax classifier, which would accumulate a much higher loss for the scores [10, 9, 9] than for [10, -100, -100]. In other words, the Softmax classifier is never fully happy with the scores it produces: the correct class could always have a higher probability and the incorrect classes always a lower probability and the loss would always get better. However, the SVM is happy once the margins are satisfied and it does not micromanage the exact scores beyond this constraint. This can intuitively be thought of as a feature: For example, a car classifier which is likely spending most of its “effort” on the difficult problem of separating cars from trucks should not be influenced by the frog examples, which it already assigns very low scores to, and which likely cluster around a completely different side of the data cloud.

Additional references

- https://cs231n.github.io